Hello everyone how are you? Today’s topic is “Hōchō (Kitchen Knife)” which is one of “Cool Japan” and it impressed me as I’ve just read the article in the paper about the book which will be published in the fall of 2018.

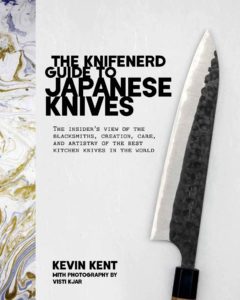

The contents of the book are about the Hōchō (kitchen knife) made in Japan, written by Mr.Kevin Kent, knife store owner from Canada.

Knifewear owner and president Kevin Kent’s fascination with handcrafted Japanese knives began while he was working as sous-chef for the legendary chef Fergus Henderson at St. John restaurant in London, England.

Back in Canada in 2007 he began selling them out of a backpack from the back of his bicycle, while working as a chef in Calgary.

Knifewear’s Knife Store (Hamono-ya) quietly opened in March 2008. The Knife Store has become a destination/hang-out for those who love Japanese steel and are addicted to sharp.

We carry knives not found in any other shop in Calgary. We like exclusive, scary sharp, high performance blades.

He considers his chef years as the best education for being an entrepreneur. Being a chef takes long hours, involves hard work, both mentally and physically, and chefs must be able to put out fires, both literal and figurative, with extreme competence.

Today, Kent is still just as obsessed with Japanese knives as the day he first held one. A couple times a year, he travels to Japan to meet with his blacksmith friends and drinks far too much sake. Each visit he learns more about the ancient art of knife-making.

Mr. Kevin Kent of the Knifeware CEO handed the commemorative plaque of the 10th anniversary to President Fujita of Tojirou company(Houcho manufacturer) in Tsubane-Sanjyou, Niigata prefecture.

Through this obsession Knifewear has expanded to include five Knifewear stores in Calgary, Vancouver, Ottawa, and Edmonton. Plans are also underway to open a store in Kyoto, Japan.

He refuses to confess how many Japanese knives he owns … but he admits the number is rather high. Follow Kevin on Twitter at @knifenerd and find out more about the stores at knifewear.com, and if you meet him in person, ask him to tell you his Lou Reed story.

We aim to offer expert knife knowledge, an enjoyable purchasing experience, after sale support and knife passion.

Contents

About “Hōchō (Kitchen Knife)”

A kitchen knife is any knife that is intended to be used in food preparation. While much of this work can be accomplished with a few general-purpose knives – notably a large chef’s knife, a tough cleaver, and a small paring knife – there are also many specialized knives that are designed for specific tasks.

Materials

Kitchen knives can be made from several different materials as follows,

★ Carbon steel is an alloy of iron and carbon, often including other elements such as vanadium and manganese.

Carbon steel commonly used in knives has around 1.0% carbon (ex. AISI 1095), is inexpensive, and holds its edge well.

Carbon steel is normally easier to resharpen than many stainless steels, but is vulnerable to rust and stains. The blades should be cleaned, dried, and lubricated after each use.

New carbon-steel knives may impart a metallic or “iron” flavour to acidic foods, though over time, the steel will acquire a patina of oxidation which will prevent corrosion.

Good carbon steel will take a sharp edge, but is not so hard as to be difficult to sharpen, unlike some grades of stainless steel.

★ Stainless steel is an alloy of iron, approximately 10–15% chromium, possibly nickel, and molybdenum, with only a small amount of carbon.

Typical stainless steel knives are made of 420 stainless, a high-chromium stainless steel alloy often used in flatware.

Stainless steel may be softer than carbon steel, but this makes it easier to sharpen. Stainless steel knives resist rust and corrosion better than carbon steel knives.

★ High carbon stainless steel is a stainless steel alloy with a relatively high amount of carbon compared to other stainless alloys.

The increased carbon content is intended to provide the best attributes of carbon steel and ordinary stainless steel.

High carbon stainless steel blades do not discolour or stain, and maintain a sharp edge for a reasonable time.

Most ‘high-carbon’ stainless blades are made of more expensive alloys than less-expensive stainless knives, often including amounts of molybdenum, vanadium, cobalt, and other components intended to increase strength, edge-holding, and cutting ability.

★ Laminated blades combine the advantages of a hard, but brittle steel which will hold a good edge but is easily chipped and damaged, with a tougher steel less susceptible to damage and chipping, but incapable of taking a good edge.

The hard steel is sandwiched (laminated) and protected between layers of the tougher steel. The hard steel forms the edge of the knife; it will take a more acute grind than a less hard steel, and will stay sharp longer.

★ Titanium is lighter and more wear-resistant, but not harder than steel. However it is more flexible than steel. Titanium does not impart any flavour to food. It is typically expensive and not well suited to cutlery.

★ Ceramic knives are very hard, made from sintered zirconium dioxide, and retain their sharp edge for a long time. They are light in weight, do not impart any taste to food and do not corrode.

Suitable for slicing fruit, vegetables and boneless meat. Ceramic knives are best used as a specialist kitchen utensil.

Recent manufacturing improvements have made them less brittle. Because of their hardness and brittle edges, sharpening requires special techniques.

★ Plastic blades are usually not very sharp and are mainly used to cut through vegetables without causing discolouration. They are not sharp enough to cut deeply into flesh, but can cut or scratch skin.

Blade manufacturing

Steel blades can be manufactured either by being forged or stamped.

★ Hand forged blades are made in a multi-step process by skilled manual labor. A chunk of steel alloy is heated to a high temperature, and pounded while hot to form it.

The blade is then heated above critical temperature (which varies between alloys), quenched in an appropriate liquid, and tempered to the desired hardness.

Commercially, “forged” blades may receive as little as one blow from a hammer between dies, to form features such as the “bolster” in a blank. After forging and heat-treating, the blade is polished and sharpened. Forged blades are typically thicker and heavier than stamped blades, which is sometimes advantageous.

★ Stamped blades are cut to shape directly from cold-rolled steel, heat-treated for strength, then ground, polished, and sharpened. Stamped blades can often, but not always, be identified by the absence of a bolster.

Type of edge

The edge of the knife can be sharpened to a cutting surface in a number of different ways. There are three main features:

★ the grind – what a cross-section looks like

★ the profile – whether the edge is straight or serrated, and straight, curved or recurved

★ away from edge – how the blade is constructed away from the edge

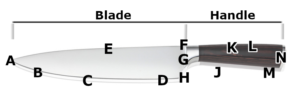

The name of its part of the knives

A Point: The very end of the knife, which is used for piercing

B Tip: The first third of the blade (approximately), which is used for small or delicate work. Also known as belly or curve when curved, as on a chef’s knife.

C Edge: The entire cutting surface of the knife, which extends from the point to the heel. The edge may be beveled or symmetric.

D Heel: The rear part of the blade, used for cutting activities that require more force

E Spine: The top, thicker portion of the blade, which adds weight and strength

F Bolster: The thick metal portion joining the handle and the blade, which adds weight and balance

G Finger Guard: The portion of the bolster that keeps the cook’s hand from slipping onto the blade

H Choil: The point where the heel meets the bolster

J Tang: The portion of the metal blade that extends into the handle, giving the knife stability and extra weight

K Scales: The two portions of handle material (wood, plastic, composite, etc.) that are attached to either side of the tang

L Rivets: The metal pins (usually 3) that hold the scales to the tang

M Handle Guard: The lip below the butt of the handle, which gives the knife a better grip and prevents slipping

N Butt: The terminal end of the handle

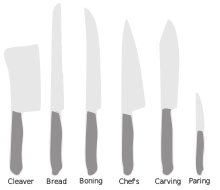

About common kitchen knives

Let’s see the kind of Kitchen knives,

★ Chef’s knife

Also known as a cook’s knife or French knife, the chef’s knife is an all-purpose knife that is curved to allow the cook to rock the knife on the cutting board for a more precise cut.

The broad and heavy blade also serves for chopping bone instead of the cleaver, making this knife the all purpose heavy knife for food preparation.

★ Paring

A paring knife is a small knife with a plain edge blade that is ideal for peeling and other small or intricate work (such as de-veining a shrimp, removing the seeds from a jalapeño, ‘skinning’ or cutting small garnishes). It is designed to be an all-purpose knife, similar to a chef’s knife, except smaller.

★ Utility

In kitchen usage, a utility knife is between a chef’s knife and paring knife in size, about 10 cm and 18 cm (4 and 7 inches) in length. The utility knife has declined in popularity, and is at times derided as filler for knife sets.

This decline is attributed to the knife being neither fish nor fowl: compared to a chef’s knife, it is too short for many food items, has insufficient clearance when used at a cutting board, and is too fragile for heavier cutting tasks, while compared to a paring knife, which is used when cutting between one’s hands, (e.g., carving a radish), the added length offers no benefit and indeed makes control harder in these fine tasks. Some designs have a serrated blade.

The term “utility knife” is often used for a non-kitchen cutting tool with a short blade which can be replaced, or with a strip of blades which can be snapped off when worn.

Besides, Bread knife, Butter knife, Cheese knives etc.,

Meat knives

★ Carving

A carving knife is a large knife (between 20 cm and 38 cm (8 and 15 inches)) that is used to slice thin cuts of meat, including poultry, roasts, hams, and other large cooked meats.

A carving knife is much thinner than a chef’s knife (particularly at the spine), enabling it to carve thinner, more precise slices.

★ Slicing

A slicing knife serves a similar function to a carving knife, although it is generally longer and narrower. Slicers may have plain or serrated edges. Such knives often incorporate blunted or rounded tips, and feature kullenschliff (Swedish/German: “hill-sharpened”) or Granton edge (scalloped blades) to improve meat separation.

Slicers are designed to precisely cut smaller and thinner slices of meat, and are normally more flexible to accomplish this task. As such, many cooks find them better suited to slicing ham, roasts, fish, or barbecued beef and pork and venison.

★ Cleaver

A meat cleaver is a large, most often rectangular knife that is used for splitting or “cleaving” meat and bone. A cleaver may be distinguished from a kitchen knife of similar shape by the fact that it has a heavy blade that is thick from the spine to quite near the edge.

The edge is sharply beveled and the bevel is typically convex. The knife is designed to cut with a swift stroke without cracking, splintering or bending the blade. Many cleavers have a hole in the end to allow them to be easily hung on a rack. Cleavers are an essential tool for any restaurant that prepares its own meat.

The cleaver most often found in a home knife set is a light-duty cleaver about 6 in (15 cm) long. Heavy cleavers with much thicker blades are often found in the trade.

A “lobster splitter” is a light-duty cleaver used mainly for shellfish and fowl which has the profile of a chef’s knife.

A cleaver is most popularly known as butcher knife which is the commonly used by chefs for cutting big slices of meat and poultry.

★ Boning

A boning knife is used to remove bones from cuts of meat. It has a thin, flexible blade, usually about 12 cm to 15 cm (5 or 6 inches) long, that allows it to get in to small spaces. A stiff boning knife is good for beef and pork, and a flexible one is preferred for poultry and fish.

★ Fillet

Fillet knives are like very flexible boning knives that are used to fillet and prepare fish. They have blades about 15 cm to 28 cm (6 to 11 inches) long, allowing them to move easily along the backbone and under the skin of fish.

About Japanese knives

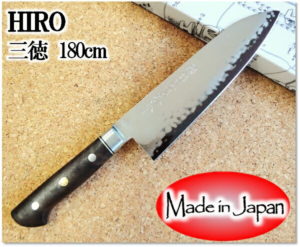

★ Santoku

The Santoku bōchō/hōchō ( Santoku means “three virtues” or “three uses”) or Bunka bōchō is a general-purpose, for cutting meat, fishes, and vegetables, kitchen knife originating in Japan. Its blade is typically between 13 and 20 cm (5 and 8 in) long, and has a flat edge and a sheepsfoot blade that curves in an angle approaching 60 degrees at the point.

The word also refers to the three cutting tasks which the knife performs well: slicing, dicing, and mincing. The Santoku’s blade and handle are designed to work in harmony by matching the blade’s width/weight to the weight of blade tang and handle, and the original Japanese Santoku is a well-balanced knife.

The Santoku has a straighter edge than a chef’s knife, with a blunted sheepsfoot-tip blade and a thinner spine, particularly near the point. From 12 cm to 18 cm (5 to 7 inches) long, a true Japanese Santoku is well-balanced, normally flat-ground, and generally lighter and thinner than its Western counterparts, often using superior blade steels to provide a blade with exceptional hardness and an acute cutting angle.

This construction allows the knife to more easily slice thin-boned and boneless meats, fish, and vegetables. Many subsequent Western and Asian copies of the Japanese Santoku do not always incorporate these features, resulting in reduced cutting ability.

Some Western Santoku-pattern knives are even fitted with kullen/kuhlen, scallops on the sides of the blade above the edge, in an attempt to reduce the sticking of foods and reduce cutting friction.

A standard in Asian (especially Japanese) kitchens, the santoku and its Western copies have become very popular in recent years with chefs in Europe and the United States.

★ Sashimi bōchō

Tako hiki, yanagi ba, and fugu hiki are long thin knives used in the Japanese kitchen, belonging to the group of Sashimi bōchō to prepare sashimi, sliced raw fish and seafood.

Yanagi ba (left) and Tako hiki (right)

Similar to the nakiri bocho, the style differs slightly between Tokyo and Osaka. In Osaka, the yanagi ba has a pointed end, whereas in Tokyo the tako hiki has a rectangular end.

The tako hiki is usually used to prepare octopus. A fugu hiki is similar to the yanagi ba, except that the blade is thinner. As the name indicates, the fugu hiki is traditionally used to slice very thin fugu sashimi.

The length of the knife is suitable to fillet medium-sized fish. For very large fish such as tuna, longer specialized knives exist, for example the almost two-meter long oroshi hocho, or the slightly shorter hancho hocho.

★ Nakiri bōchō

Nakiri bocho and usuba bocho are Japanese-style vegetable knives. They differ from the deba bocho in their shape, as they have a straight blade edge suitable for cutting all the way to the cutting board without the need for a horizontal pull or push.

The deba bocho is a heavy blade for easy cutting through thin bones, the blade is not suitable for chopping vegetables, as the thicker blade can break the vegetable slice.

These knives are also much thinner. The nakiri bocho and the usuba bocho have much thinner blades, and are used for cutting vegetables.

Nakiri bocho are knives for home use, and usually have a black blade. The shape of the nakiri bocho differs according to the region of origin, with knives in the Tokyo area being rectangular in shape, whereas the knives in the Osaka area have a rounded corner on the far blunt side

.

The cutting edge is angled from both sides, called ryoba in Japanese. This makes it easier to cut straight slices.

Nakiri bocho, Osaka style on the left and Tokyo style on the right

Usuba bocho are vegetable knives used by professionals. They differ from the Nakiri bocho in the shape of the cutting edge. While the nakiri bocho is sharpened from both sides, the usuba bocho is sharpened only from one side, a style known as kataba in Japanese.

The highest quality kataba blades even have a slight depression on the flat side. This kataba style edge gives better cuts and allows for the cutting of thinner slices than the ryoba used for nakiri bocho, but requires more skill to use.

The sharpened side is usually the right side for a right hand use of the knife, but knives sharpened on the left side are also available for left hand use.

The usuba bocho is also slightly heavier than a nakiri bocho, although still much lighter than a deba bocho.

Usuba bocho (knives) are Japanese knives used primarily for chopping vegetables. Both the spine and edge are straight, making them resemble cleavers, though they are much lighter.

Deba bocho (knives) are Japanese knives used primarily for cutting fish. They have blades that are 18 cm to 30 cm (7 to 12 inches) long with a curved spine.

Finally, why don’t you have a try how sharp knives made in Japan?

Regarding the blacksmith, you’ll enjoy these websites too, One is KATANA (JAPANESE SWORD)

and the Other; Swedish-Japanese swordsmith forges his destiny in Japan after trial by fire