Hi, how is it going? Today’s topic is “Kobudō” that is one of “Cool Japan” and the basic of Japanese martial arts such as “Judō”, “Karate”, “Kendō”,”Kyudō” and so on.

Contents

What’s “Kobudō”?

Kobudō (old martial arts) is a collective term for Japanese traditional techniques with bare hands like Karate and for the use of armour, blades, firearms, and techniques related to combat and horse riding.

Kobudō, the term appeared in the first half of the seventeenth century. Kobudō marks the beginning of the Tokugawa period (1603–1868) also called the Edo period, when the total power was consolidated by the ruling Tokugawa clan.

Yabusame archer on horseback, one of an ancient combat forms

The term often refers to martial arts established before the Meiji Restoration of the 19th century. Since the Muromachi period, swordsmanship, jiu-jitsu, martial arts, archery, artillery, etc. have been technicalized and systematized as various schools.

The term Kobudō (ancient martial arts) contrasts with Gendai budō (modern martial arts) or shinbudō (new martial arts) which refer to schools developed since the Meiji era.

Whereas modern martial arts are designed to develop human skills and physical and mental training from the physical point of view, focusing on sports-related competitions and constructing technical systems (e.g., judō and kendō), old martial arts are fundamentally not intended with an outcome of a winning match.

Training was for the sake of it. Dangerous techniques that are excluded from modern martial arts include various hidden weapons, medicinal methods, and magic.

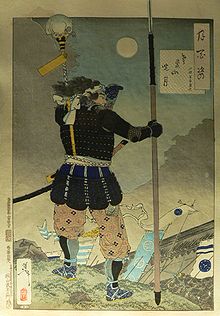

Kenjutsu, the oldest schools of swordsmanship

Old martial arts are linked to Zen and Buddhism. It may also include irrational movements whose original meaning have been lost even to those who are masters of the school, or movements added for aesthetic reasons during the peaceful Edo period.

The system of kobudō is considered in following priorities order: 1) morals, 2) discipline 3) aesthetic form.

Examples of taught skills are follows

● Bōjutsu, using Bō, a staff(A long stick) weapon . Staffs have been in use for thousands of years in East Asian martial arts like Silambam. Some techniques involve slashing, swinging, and stabbing with the staff. Others involve using the staff as a vaulting pole or as a prop for hand-to-hand strikes.

Today bōjutsu is usually associated either with Okinawan kobudō or with Japanese koryū budō. Japanese bōjutsu is one of the core elements of classical martial training.

Thrusting, swinging, and striking techniques often resemble empty-hand movements, following the philosophy that the bō is merely an “extension of one’s limbs”. Consequently, bōjutsu is often incorporated into other styles of empty-hand fighting, like traditional Jiu-jitsu, and karate.

●Jujutsu (jiu-jitsu is most widely used in Germany and Brazil) is a Japanese martial art and a method of close combat for defeating an opponent in which one uses either a short weapon or none.

“Jū” can be translated to mean “gentle, soft, supple, flexible, pliable, or yielding”. “Jutsu” can be translated to mean “art” or “technique” and represents manipulating the opponent’s force against themselves rather than confronting it with one’s own force. Jujutsu developed to combat the samurai of feudal Japan as a method for defeating an armed and armored opponent in which one uses no weapon, or only a short weapon.

Because striking against an armored opponent proved ineffective, practitioners learned that the most efficient methods for neutralizing an enemy took the form of pins, joint locks, and throws. These techniques were developed around the principle of using an attacker’s energy against him, rather than directly opposing it.

There are many variations of the art, which leads to a diversity of approaches. Jujutsu schools (ryū) may utilize all forms of grappling techniques to some degree (i.e. throwing, trapping, joint locks, holds, gouging, biting, disengagements, striking, and kicking).

In addition to jujutsu, many schools teach the use of weapons. Today, Jujutsu is practiced in both traditional and modern sports forms.

Derived sport forms include the Olympic sport and martial art of judo, which was developed by Kanō Jigorō in the late 19th century from several traditional styles of jujutsu, and Brazilian jiu-jitsu, which was derived from earlier (pre–World War II) versions of Kodokan judo.

●Jittejutsu is the Japanese martial art of using the Japanese weapon jitte. Jittejutsu was evolved mainly for the law enforcement officers of the Edo period to enable non-lethal disarmament and apprehension of criminals who were usually carrying a sword.

Besides the use of striking an assailant on the head, wrists, hands and arms like that of a baton, the jitte can also be used for blocking, deflecting and grappling a sword in the hands of a skilled user.

●Kenjutsu is the umbrella term for all (ko-budō) schools of Japanese swordsmanship, in particular those that predate the Meiji Restoration. Some modern styles of kendo and iaido that were established in the 20th century also included modern forms of kenjutsu in their curriculum.

Kenjutsu, which originated with the samurai class of feudal Japan, means “methods, techniques, and the art of the Japanese sword.” This is opposed to kendo, which means “the way of the sword” and uses a bamboo sword (shinai) and protective armour (bōgu).

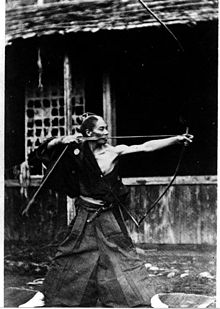

●Kyūjutsu (“art of archery”) is the traditional Japanese martial art of wielding a bow (yumi) as practiced by the samurai class of feudal Japan. Although the samurai are perhaps best known for their swordsmanship with a katana (kenjutsu), kyūjutsu was actually considered a more vital skill for a significant portion of Japanese history.

During the majority of the Kamakura period through the Muromachi period (c.1185–c.1568), the bow was almost exclusively the symbol of the professional warrior, and way of life of the warrior was referred to as “the way of the horse and bow”.

●Naginatajutsu is the Japanese martial art of wielding the naginata. This is a weapon resembling the medieval European glaive. Most naginatajutsu practiced today is in a modernized form, a gendai budō, in which competitions also are held.

●Naginatajutsu is the Japanese martial art of wielding the naginata. This is a weapon resembling the medieval European glaive. Most naginatajutsu practiced today is in a modernized form, a gendai budō, in which competitions also are held.

●Ōzutsu(artillery) hand cannon was first used during the Sengoku period in the 16th century; and its use has continued to develop.

●Sōjutsu, meaning “art of the spear”, is the Japanese martial art of fighting with a Japanese spear.

●Tantōjutsu is a Japanese term for a variety of traditional Japanese knife fighting systems that used the tantō, (a short knife or dagger). Historically, many women used a version of the tantō, called the kaiken, for self-defense, but the onna-bugeisha, (warrior women) who were part of the samurai class, learned one of the tantojutsu arts to fight in battle.

●Yabusame is a type of mounted archery in traditional Japanese archery. An archer on a running horse shoots three special “turnip-headed” arrows successively at three wooden targets.

This style of archery has its origins at the beginning of the Kamakura period. Minamoto no Yoritomo became alarmed at the lack of archery skills his samurai possessed. He organized yabusame as a form of practice.

Nowadays, the best places to see yabusame performed are at the Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū in Kamakura and Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto (during Aoi Matsuri in early May). It is also performed in Samukawa and on the beach at Zushi, as well as other locations.

Ms Alice Iwamoto’s story from the spirit of Kobudō

In a society that values prescribed pathways to success, carving one’s way as an outsider is rarely the first choice in Japan, but for Alice Iwamoto, who is fashioning an independent acting career from scratch, it’s been the only choice.

To achieve her goal, the 27-year-old former dancer has spent the two years since arriving from Australia feverishly acquiring the various skills that will allow her to make it as an action actor in Tokyo’s growing freelance film-making industry.

Aspiring actress Alice Iwamoto practices a kobudo martial art movement

In retrospect, it seems fitting that someone seeking diverse skills found kobudō, perhaps the most esoteric of Japanese martial arts. Translated as “old martial arts,” kobudō is a collective term for Japanese traditional techniques used in combat and martial arts established before the Meiji Restoration (1868).

“Kobudō was a discipline developed to train warriors to be flexible, to survive regardless what weapon was at hand,” says Iwamoto’s shihan (senior instructor), Hiroyuki Yashiro of the dojo Musubi An, in a recent interview. “A warrior might enter combat with a sword, but if he lost it he would need to know how to fight on with a pole. If he lost that, he would need to battle with his bare hands.”

Although kobudō involves fundamental prescribed movements, known as kata, to understand the building blocks of the different skills, Yashiro says the goal is integrating one’s self into one’s skills, and vice versa.

“If everyone is practicing the same kata, moving at identical angles, that’s boring. We’re not robots,” he says. “You have to adapt and develop as an individual.”

Iwamoto, whose career is slowly developing momentum through a variety of channels making use of either her language skills or her action work, has a history of improvising from an early age.

At the age of 8, she moved with her family from Fukuoka to Queensland, Australia, to a rural community that, she says, was inhospitable to Asians. After a year of studying English, she and her older sister entered the local school and it became a daily struggle.

Frustrated and isolated, she often invented ways to learn and express herself through play acting. She and her sister created their own school at home where Iwamoto played the teacher and her sister took on the roles of the different students. When she finished high school and left home, Iwamoto approached life in high gear.

“I just wanted to do everything I couldn’t do the past 10 years. I started working at two or three jobs, while going to university,” she says. “I started dancing. I don’t think the instructors believed me when I said I wanted to be a professional dancer, because usually you start at a young age to get into the professional world. I was 18 years old already, but I was very determined to prove them wrong.”

Iwamoto’s desire to make up for lost time, however, led to overtraining and an injury that ended her hopes of a dance career. When she graduated from university, she had no serious job prospects and without feeling any attachment to Australia, she decided to go to Japan.

Two weeks after she considered the idea, she was in Tokyo, but without the Japanese education and the level of language skills she needed.

“I had to find a job quickly and the only things I could do were translation or teaching English, so I did those two,” she recalls. “But I felt something was missing — my creative outlet, expressing something with my body, whether that be dance, acting, acrobatics, I didn’t know. I think it occurred to me that I really wanted to try acting, acrobatics and stunts.”

Within two months, she had worked out a path to follow. As she added skills to her portfolio and started finding relevant work, she also began to find other ways to set herself apart from her peers.

Alice Iwamoto (left) with her teacher Hiroyuki Yashiro (center) and Musubi group leader Yui.

Although fighting and sword play are a staple of action acting in Japan, many actors get by just mimicking the movements, but Iwamoto wanted to achieve a higher level of realism. Having years of experience improvising with her creative side, her discovery of a discipline of improvisation in battle seemed an ideal match.

Like Iwamoto, the woman who leads her Musubi An kobudō group, Yui, and Yashiro, came to the martial art through dissatisfaction with the superficiality of fighting in Japanese acting. Yui and Yashiro both practiced kendo but found an authenticity in kobudō they felt could bring sincerity to their acting.

“In kobudō, if you are only mimicking a move, memorizing it and moving on to the next, it comes across as fake. But the kata within kobudō are deep and if you really work to understand what goes into one, then you can distinguish between what is real and what is not,” says Yui.

“That is the same in acting. One can tell when acting rings true. Even if the same lines are spoken in conjunction with the same movements, people can tell if it is imitative or not.”

Yashiro says kobudō has a side to it that sets it apart from other martial arts disciplines.

“Coming from an acting background, I recognize kobudō has a space for self-expression. Martial arts depend on perfecting kata, and so often people tend to fixate on them,” he says.

“Allowing for freedom, however, creates the possibility of discovery. Actors, singers and dancers have freedom of expression and in kobudō that is also true. If we demand rigid observance of form, it can’t grow.”

Iwamoto describes kobudō’s benefits as “perseverance, diligence and cognitive flexibility.” And in her daily battle, those are real assets.

“I had to keep going, emotionally. I wouldn’t give up the creative outlet I wanted to do, she says of her experience. “I want to find that happy medium, where I’m physically well, I can pay the bills (through work) and do the training — getting that balance.”

Finally, “Samurai“, “Kendo“,”judo“, “kyudo“, “Aikido“, “Karate“, and “Sumo” those are well worth visiting, thanks