Hi everyone how are you doing? Today’s theme is “Umami” (savory taste), in which is significantly influential on food.

Contents

What’s “Umami” (savory taste)?

Savory taste is one of the five basic tastes (together with sweetness, sourness, bitterness, and saltiness).

It has been described as savory and is characteristic of broths and cooked meats.

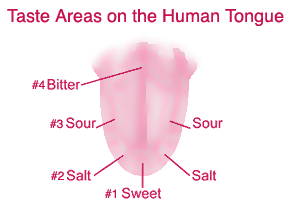

Sweet, Salt, Sour、 Bitter, THAT’s ALL ?

You have ever seen the above image that was published by Dr. Bowling who taught at Harvard University and Clark University at that time in 1942 and the illustration shows our tongue feels differently depending on the place.

According to the recent information, however, this was not right.

The newest publication says that there is not the distinctive taste area of the tongue but feel a little even though there are approximately 10,000 gustatory or taste buds of our tongue.

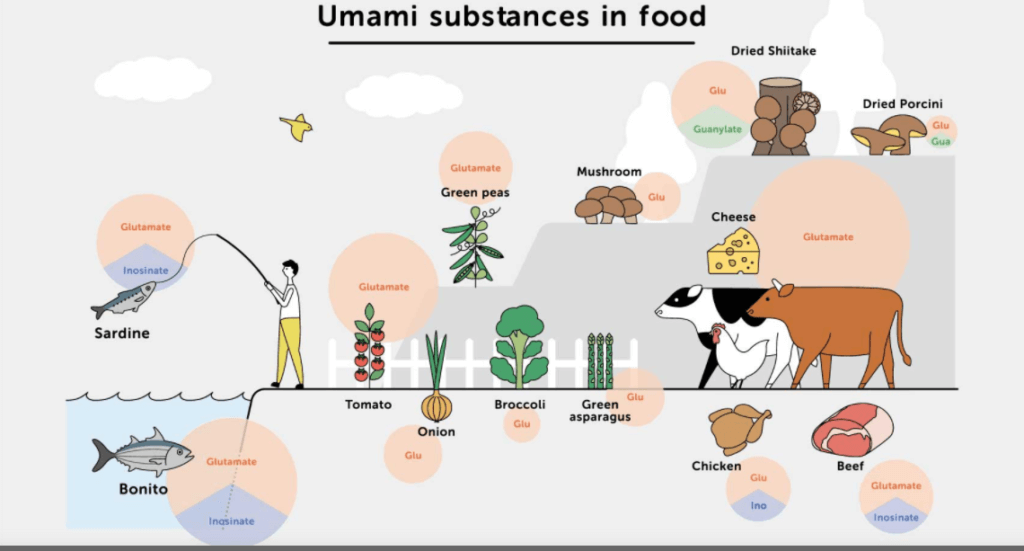

Foods that have a strong umami flavor include broths, gravies, soups, shellfish, fish and fish sauces, tomatoes, mushrooms, hydrolysed vegetable protein, meat extract, yeast extract, cheeses, soy sauce, and human breast milk.

No, we have 5 senses of taste of our tongue, that is “Umami” which is now an international word.

What’s the fifth sense, Umami, then?

Umami has been variously translated from Japanese as yummy, deliciousness or a pleasant savoury taste, and was coined in 1908 by a chemist at Tokyo University called Kikunae Ikeda.

He had noticed this particular taste in asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat, but it was strongest in dashi – that rich stock made from kombu (kelp) which is widely used as a flavour base in Japanese cooking.

So he homed in on kombu, eventually pinpointing glutamate, an amino acid, as the source of savoury wonder.

He then learned how to produce it in industrial quantities and patented the flavour enhancer MSG (monosodium glutamate).

How to find the Umami taste?

Professor Kidunae Ikeda comes home from the physics faculty at the Tokyo Imperial University and sits down to eat a broth of vegetables and tofu prepared by his wife.

It is – as usual – delicious. The professor, a mild, bespectacled biochemistry specialist, turns to Mrs Ikeda and asks – as spouses occasionally will – what is the secret of her wonderful soup?

Mrs Ikeda points to the strips of dried seaweed she keeps in the store cupboard.

This is kombu, a heavy kelp. Soak it in hot water and you get the essence of dashi, the stock base of the tangy broths and consommés the Japanese love.

This is the professor’s ‘Eureka!'(I’ve found) moment. Mrs Ikeda’s kombu is to lead him to a discovery that will make his fortune and change the nature of 20th-century food.

In time, it would bring about the world’s longest-lasting food scare, and as a result, kick-start the age of the rebel consumer. It was an important piece of seaweed.

Professor Ikeda was one of many scientists at the turn of the century working on the biochemical mechanics which inform our perception of the world.

By 1901 they had drawn a map of the tongue, showing, crudely, the whereabouts of the different nerve endings that identify the four accepted primary tastes, sweet, sour, bitter and salty.

But Ikeda thought this matrix missed something. ‘There is,’ he said, ‘a taste which is common to asparagus, tomatoes, cheese and meat but which is not one of the four well-known tastes.’

He decided to call the fifth taste ‘umami’, a common Japanese word that is usually translated as ‘savoury’ or, with more magic, as ‘deliciousness’.

By isolating umami, Ikeda who had picked up some liberal notions while studying in Germany hoped he might be able to improve the standard of living of Japan’s rural poor.

And so he and his researchers began their quest to isolate deliciousness.

By 1909 the work on kombu was complete. Ikeda made his great announcement in the august pages of the Journal of the Chemical Society of Tokyo.

He had isolated, he wrote, a chemical with the molecular formula C5H9NO4. This and the substance’s other properties were exactly the same as those of glutamic acid, an amino acid produced by the human body and present in many foodstuffs.

When the protein containing glutamic acid is broken down by cooking, fermentation or ripening – it becomes glutamate.

‘This study,’ concluded Professor Ikeda in triumph, ‘has discovered two facts: one is that the broth of seaweed contains glutamate and the other that glutamate causes the taste sensation “umami”.’

The next step was to stabilise the chemical. This was easy: mixing it with ordinary salt and water made monosodium glutamate – a white crystal soluble in water and easy to store.

By the time he published his paper, the professor had, wisely, already patented MSG. He began to market it as a table condiment called Aji-no-moto (‘essence of taste’) that same year.

It was an instant success, and when Kidunae Ikeda died in 1936 he was a rich man: he remains, as every Japanese schoolchild knows, one of Japan’s 10 greatest inventors.

The food chemicals giant Ajinomoto Corp, now owned by General Foods, pumps out a third of the 1.5 million tons of monosodium glutamate we eat every year – from India to Indonesia ‘Ajinomoto’ means MSG.

Eat Well, Live Well

You have probably seen or heard the above Ajinomoto Corp’s slogan through TV, radio, or other social media.

Ajinomoto Co., Inc.(“essence of taste”) is a Japanese food and chemical corporation which produces seasonings, cooking oils, TV dinners, sweeteners, amino acids, and pharmaceuticals, and it is the trade name for the company’s original monosodium glutamate (MSG) product.

Ajinomoto operates in 35 countries, employing around 32,734 people as of 2017. Its yearly revenue in the fiscal year of 2017 stands at around US$10.5 billion.

3 major taste ingredients

Besides Glutamic acid, there are two more great taste ingredients,

they are inosinic acid mostly from dried bonitos, Katsuobushi

and guanylic acid mainly from dried mushroom, Hoshi-Shiitake.

In closing, please have a typical Japanese dish in which you could enjoy its taste to your heart, thanks.

Besides, “Dashi(Cooking stock/broth): The Secret Ingredient of Japanese Cuisine to be well worth browsing, thanks