Hello everyone how are you? Toddy’s subject is Sōshiki (Funeral), which is one of very important events in our human life.

So let’s talk about the Sōshiki(Funeral) of the Buddhist ceremony in order.

Contents

Indifference to religion

We Japanese, frankly speaking, are tend to show indifference to any religions in daily life, however, we have taken on a variety of different religious practices, such as Christian-styled weddings in most cases or/and local Shintō rituals.

But as far as recent funerals are concerned, we are absolutely Buddhist styled funerals carried out by priests at a sophisticated funeral hall.

On the other hand, funerals at home or temples are drastically decreasing nowadays.

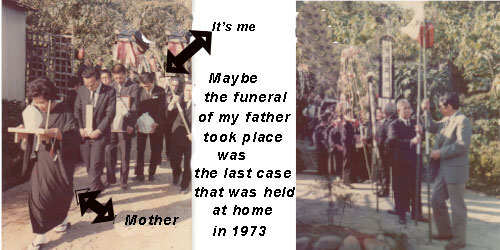

The following photo, however, is rare and maybe the last funeral ceremony in Japan that took place at home for my father in October, 1973.

Please allow me to use images from my mother’s funeral on January 28, 2012 at her age of 99 to help you understand more easily.

At the same time, funerals in Christianity, Muslim, and Shinto Shrine are very few to take place.

A Buddhist Majority

Japanese society accommodates a wide variety of faiths. When a loved one passes, however, the majority of Japanese choose to hold a Buddhist Sōshiki(Funeral).

According to a survey by the Japan Consumers’ Association, 92.1% of funerals are Buddhist, 2.4% Shintō, and 5.5% other religions and/or nonreligious.

While Buddhism is important to many, it is often only at the end of life and special anniversaries (hōyō) marking the passing of a loved one that people turn to their parish temple to ask a priest to chant prayers and conduct rites for the departed.

This style of religious observance is facetiously referred to by some as “funeral Buddhism.”

Services have been normally held at a temple, the deceased’s home so far from the olden times but recently many people seem to change to use a funeral hall.

How is generally Sōshiki (Funeral)Services held?

Although Buddhist funeral rites vary by denomination and region, in general the body after death is washed and laid out with the head toward the north.

After death there is a ceremony called “Matsugo-no-mizu” (Water of the last moment) where lips of the deceased are moistened with little bit of water.

A small table is put next to the bed with deceased. On such table there are some flowers, incense and a candle.

Some people put a knife on the chest of deceased. This knife should defend her or him from the evil spirits.

Family of the deceased then informs cousins and friends. As a sign that someone died family puts a white paper lantern in front of the house. A death certificate is issued.

Family also contacts a priest of the local temple and a funeral hall to make arrangements for the funeral.

Body of the deceased is washed. Little bit of cotton or gauze is put in the orifices. The deceased female wears are a kimono. Men sometimes wear it too.

But usually dead male wears a suit. To improve the look of the deceased a make-up may be applied.

The body is then put on a dry ice in the casket/coffin. It is a tradition that few other things are placed in the casket too.

They are a white kimono, six coins for the crossing of the Sanzu River (“Sanzu-no-kawa”) or River of Three Crossings and several objects the deceased used to love like for example sweets.

When the casket is ready it is put on an altar.

The second stage in the funeral activities is the wake(Otsūya in Japanese). Traditional colour of sorrow in Buddhism is white. Still most of people in Japan today wear black when attending the wake .

People at the wake sometimes carry set of prayer beads called “juzu”. Juzu is similar to the Rosary.

People arriving at the wake bring condolence money or “koden” in a special envelope that has a black and white ribbon wrapped around it. The amount of money is written on the envelope.

Before her cremation

People are seated. Family and close relatives sit in the first row. The Buddhist priest will then chant a section from a “sutra” (religious scriptures).

In front of the deceased there is an incense urn. The family members will offer an incense three times. Other people at the wake will offer incense in the place behind seats where the family members are seated.

Last farewells from family and relatives before going to the crematorium

The priest completes the sutra and that way the wake ends. When leaving each guest gets a present. The present has a value between 25% and 50% of the money people gave as condolence money.

The vigil for the deceased is held by the family and close relatives during the night before the funeral.

The Sōshiki(Funeral) is held the day after the wake. Following the service the body is cremated, after which family members use special chopsticks to place pieces of bones in a small urn (kotsutsubo).

A 2016 report by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare showed that 99% of Japanese burials involve cremation although we used to bury the corpse under the ground until recently.

Depending on their relation to the deceased, friends and family may choose to attend either the wake or the funeral service.

Typical mourning attire (mofuku) is a black dress for women and a black suit and tie for men. Those attending also commonly carry a Buddhist rosary known as a juzu. Dress at a wake is less formal.

The urn stays on an altar in family home for 35 days. Incense sticks or “osenko” are kept burning all the time. Then the urn is carried to the cemetery.

Some people carry the urn to the cemetery immediately after the urn is ready.

“Haka” family grave,gravestone

“Haka” family grave,gravestone

On the side of monument sometimes you may see engraved the name of the person who paid for the monument. The names of persons buried in the grave can be written on the monument.

Memorial services differ from region to region. During first week after death they are held every day. There are special services held on the 7th, 49th and 100th day.

There is a traditional memorial service performed during the Obon festival.

Japan’s Evolving Sōshiki(Funeral) Business

Japan is a country of high technology. So, let’s just mention very expensive graves who include small pc with a touch screen showing all sort of details about the deceased – a her or his photo, different messages, a family tree etc.

Demographic aging and other social transformation under way in Japan are occasioning drastic changes in funeral practices.

People are increasingly opting for smaller funerals and for greater personalization of services. Also on the increase is the number of uncared-for graves.

Responses to Japan’s funerary issues include new options such as space burial, where for a fee a portion of a loved one’s ashes can be launched into the cosmos.

Two hundred twenty companies from Japan’s funeral industry took part in a trade show in December 2015 at the Tokyo Big Sight exhibition complex.

Capturing the most attention at the show were space funerals. The services on offer included encapsulating the deceased’s ashes and launching the capsules into space—a celestial version of scattering ashes at sea.

Balloons for carrying a loved one’s ashes aloft

Another US celestial funeral operator, Elysium Space, has been marketing its services in Japan since October 2013.

These include launching remains and releasing them in space, whereupon they circle the Earth before plummeting through the atmosphere like a shooting star.

Balloons for carrying a loved one’s ashes aloft

Another US celestial funeral operator, Elysium Space, has been marketing its services in Japan since October 2013.

These include launching remains and releasing them in space, whereupon they circle the Earth before plummeting through the atmosphere like a shooting star.

The firm charges ¥300,000 for its Shooting Star Memorial service.

Family Sōshiki(Funeral)

A “family funeral” refers to a small-scale funeral where close relatives and friends are invited.

While there is no specific definition or set of rules for a family funeral, it generally refers to a funeral with around 10 to 30 attendees.

The advantages of a family funeral include the opportunity to bid a leisurely farewell to the deceased and the minimal preparation and consideration required for the attendees.

Disadvantages may include a reduction in condolence money received and the need to carefully consider the extent to which the news of the passing is shared.

The flow of a family funeral is similar to a traditional funeral, but certain aspects may be omitted due to the smaller scale. The typical sequence of a family funeral is as follows:

Passing Away: Confirmation of Death ~ Funeral Arrangements

Wake: Purification Ritual ~ Vigil Meal

Funeral: Funeral Service ~ Memorial Meal

Cremation: Cremation at the Crematorium ~ Collection of Ashes

With the aging of the baby boomers, funerals will increase enormously.

With this increase, we can expect to see an explosion of small family funerals, rather than the showy funerals we have seen in the past.

Thanks a lot for browsing.

-1.jpg)