Ladies and gentlemen, how are you? Today, I’d like to talk about a traditional Kekkon (Marriage) system that have drastically changed around the time of World War Two.

Contents

Omiai (arranged matchmaking)

It is related to marriage, have you ever heard of Omiai (arranged matchmaking)? In prewar period, Omiai was in most cases a custom of a kind of necessary event before marriage.

In fact, marriage has been characterized as centering on arranged marriage (Omiai), in which a man, a woman, and their families are formally introduced to each other by a Nakodo (go-between).

Allied to this is the traditional Japanese concept of marriage as the creation of links between two households rather than the joining of two individuals.

Put simply, marriage has traditionally been more of a family affair in Japan than it has in most Western cultures.

However, the Japanese attitudes to marriage have changed in response to a host of new social situations, some of which are the result of influence from the West.

While traditional ideas concerning the mechanics of making a match in Japan have not been completely abondoned, marriage in contemporary Japan is a private decision between two people.

Households, in particular the parents of a couple contemplating marriage, do not have as final a say in the matter as they did 50 years ago, and the function of the go-between has in many cases shrunk to a largely ceremonial role.

How has Kekkon (Marriage) been changed after the war?

In the Meiji Restoration of 1868, our country began an all-out effort to industrialize and catch up with the West.In the Meiji period, under the Civil Code of 1898 marriage was legally conducted under the so-called Ie (houshold) system, which necessitated the agreement of the heads of the two households involved in a marriage.

Under Meiji civil law husband and wife were far from equal, through marriage, the wife lost her legal capacity to engage in property transactions, management of her own property came under her husband’s control, and only the wife had the duty of chastity.

After the Second World War, the new Civil Code of 1947 abolished the Ie system and eliminated the legal inequality of husband and wife.

Post World War Two

Though the legal requirements of marriage in Japan changed radically after the war, marriage practices were slower to respond to outside influence.

The tradtional marriage pattern continued relatively unchanged, especially in high-status families.

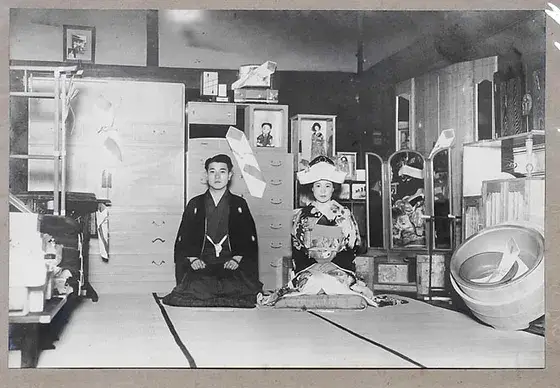

Here’s a good examaple of wedding style of different Japanese style (till Showa ~1989) and Western style (Heisei 1989~2019) as follows,

Differences between Japanese and Western-style bridal gowns through the times Left Japanese-style (1971) Wife Right Western-style (2002) Daughter

Left Japanese-style (1971) Wife Right Western-style (2002) Daughter

Very few Japanese of the mid-20th century expected to find a spouse through casual meeting or dating.

More Japanese now say they prefer a Renai Kekkon (love marriage) over the Omiai. Individual choice has in many cases become the deciding factor in settling on a marriage partner, and the level of malilial involvement in the marriage process has come to resemble that found in Western countries.

Wedding ceremonies are diverse in style

A little over one millon couples get married in 1972 when it was at the peak year in our country and then the number of marriage couples have gradually gotten less to about 600,000 in 2017 reflecting its population has been decreasing.

Married couples were not Christian

Married couples were not Christian

As shown the above photo, the ceremony is being held at a church. It’s said that more than 60 percent of all Japanese wedding ceremonies are Christian-style. And many Japanese women dream of wearing a Western-style wedding dress.

Shinto Wedding

This is a Shinto wedding, held at a shrine. The couple take matrimonial vows before a deity of Japan’s ancient religion.

In this setting, the bride is usually dressed head-to-toe in white. White is a sacred colour representing absolute purity. It symbolizes her immaculate heart, which, from now on, will take on the colour of the family she’s marrying into.

There’s a ritual involving sake at this type of wedding. The bride and groom sip sacred sake-three sips from each of three cups, making nine sips in all. This repetition of the lucky number of three expresses gratitude to ancestors and a wish for many descendants.

History of marriage

Approximately 1,000 years ago, during the age of the Heian (794 – 1185」nobility, it was common for an aristocratic couple to live separately and for the husband to visit his wif only at night. Back then, Japanese aristocratic society was polygamous, and a man might visit several different wives-matrilocal/uxorilocal in another word.

In the 13th century, when the clans with the greatest military strength flourished, it became rypical for bride to move in with the groom’s family-patrilocal/virilocal.

She was expected to take care of domestic matters and to guarantee the prosperity of the clan by bearing strong sons.

During the Edo (1603-1868) period, emphasis was placed on the relationship between two families, as opposed to two individuals. This resulted in more marriages that ignored the feelings of the couple themselves.

The growing desire for relationships based on personal feelings gave rise to numerous works of fiction that dealt with-and romanticized-forbidden love. Some were presented as Bunraku and Kabuki plays, and received accolades from the masses.

Huge changes came to the institution of marriage in Japan following the Second World War. In 1946, the new constitution was promulgated. It proclaimed that marriage should be freely entered into by a man and a woman.

Today, most Japanese get married of their own free will, regardless of their parents’ opinion. Along with the trend towards globalization, more and more Japanese are tying the know with partners of different nationality. Slowly but surely, the institution of marriage is changing to match the times.