Hi how are you? Today’s topic is about Swordsmith from Switzerland.

In Shobara City, Hiroshima Prefecture, there is the “Zenbaku Japanese Sword Forging Hall,” where young people undergo training under the guidance of the unmonitored swordsmith, Kubo Zenbaku. Among them is Johann Loitweiler, a Swiss native.

We conducted an interview with Johann Loitweiler and Kubo Zenbaku regarding the training of a swordsmith.

Right: Johann Loitweiler

Born in 1989. Swiss native. Currently in his fourth year of training.

Left: Kubo Zenbaku, Swordsmith

Born in 1965.

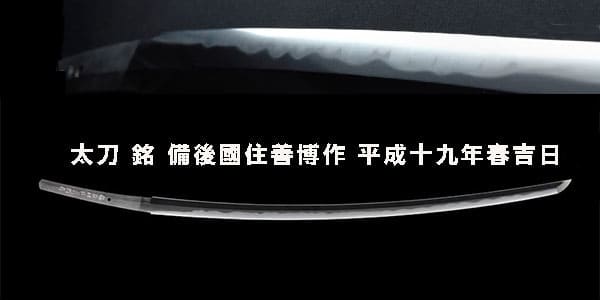

Aspiring to reproduce famous swords from the Kamakura period, he entered the apprenticeship of Yoshihara Yoshihito, a swordsmith. He succeeded in reproducing the famous swords in 2007.

Received unmonitored certification in 2017.

Table of Contents

1. Leading up to becoming an apprentice

2. Training as a swordsmith

3. Becoming a foreigner in the world of swordsmithing

Contents

Leading up to becoming an apprentice

(Qestion、from now on, “Question will be shown as “Q”) Johann Loitweiler-san(we put “san” after name to show a kind of respect), you are from Switzerland and came to Japan five years ago. Could you tell us about your background and experiences before coming to Japan?

(Johann Loitweiler, from now on, it will be shown as “Johann”) I grew up in a household where my mother was a dental assistant and my father was a school caretaker.

Perhaps the most influential figure in my life was my older brother, who was three years older than me and began an apprenticeship at an ironworks.

He would often come home and talk about his work, and he even taught me some basic metalworking, which was probably my first encounter with metal.

Thanks to him, I also began an apprenticeship in the same field when I was 14. My first encounter with Japanese swords was around the age of 15 at an exhibition.

They were likely replicas, but they had the shape of Japanese swords, and I became highly interested. At the time, I was also working with metal, so there was a connection, and I started to find swords fascinating.

(Q) What is the general perception of Japanese swords in Switzerland?

(Johann) In general, they are seen as exceptionally well-crafted blades and regarded as beautiful works of art.

Not only in Switzerland but probably throughout Europe, there is an image of Japanese swords as cool weapons wielded by samurai. The artisans who craft them are also seen as highly skilled.

(Q)Is there no association of Japanese swords with being weapons and fearsome?

(Johann) No, not really. Japanese people tend to think that way. Of course, they are weapons, but there haven’t been people here who were killed by swords, so I don’t think there’s that fearful image.

(Q) What led you to decide that you wanted to become a swordsmith after seeing swords at the exhibition at the age of 15?

(JohannJ) I didn’t initially set out to become a swordsmith. Besides, there were no foreigners who had become swordsmiths, so I didn’t know how I could start my apprenticeship or training.

So, when I became interested in swords and wanted to get closer to them, the only available option seemed to be practicing Iaido (a Japanese martial art focused on sword drawing techniques).

So I began practicing Iaido and Kenjutsu (swordsmanship). This was when I was 18 years old. I continued practicing them for 10 years before coming to Japan.

We use Japanese during training at the dojo(hall), terms like ma-ai and suntome are all used directly in Japanese, so I became interested in the language.

Starting around the age of 20, I began studying Japanese and calligraphy.

(Q) So, you stayed in Switzerland until around the age of 28.

(Johann) It wasn’t easy to leave Switzerland. I had work commitments, and I also had to fulfill my military service. So, there were many things I had to take care of. I wanted to come to Japan earlier.

I visited Japan for the first time as a tourist in 2012, and it had a profound impact on me. Within a week of being in Japan, I realized that Japan was where I belonged, and in my mind, my life had meaning because I was here.

If I had stayed in Switzerland, I couldn’t have lived the life I wanted to lead. It was a sort of revelation, an understanding that “I get it; it’s like that.”

So, I returned to Switzerland, and between 2012 and 2017, it was a period where I really wanted to come to Japan but couldn’t.

It might have been the most challenging time of my life with many difficulties. But now, I’m the happiest I’ve ever been (laughs).

(Q) So, after overcoming that difficult period and completing your military service, you were finally able to come to Japan, and you decided to start your training?

(Johann) At first, when I arrived in Japan, I attended a Japanese language school for about a year and a half. I wanted to polish my Japanese language skills, so I studied every day.

I believe that language is crucial. If I couldn’t communicate with my master, it would be meaningless. As a swordsmith, there is a lot I have to learn on my own because my master won’t teach me everything step by step.

So, I thought I needed to be able to read books in Japanese, and that’s why I decided to master the language. From there, I had the opportunity to start my apprenticeship.

(Q) How did you decide where to apprentice?

(Johann) There is a training program for prospective apprentices run by the All Japan Swordsmith Association, and I participated in that program, where I first met my master.

Initially, I didn’t plan to come here, but every day I think it was a great decision to come here. I had the opportunity to start my apprenticeship due to my connection with my master.

Training as a Swordsmith

(Q) What does a typical daily schedule for your training look like?

(Johann) It varies every day, but during the first and second years of my training, there wasn’t much I could do, so I started the day by cleaning.

After that, I would work on small projects like making paper knives or basic items. I couldn’t make much more than that.

I would also cut charcoal. So, in the beginning, the mornings were dedicated to blacksmithing, and the afternoons to cutting charcoal.

Recently, it’s a bit different. As I’ve become more skilled, I can work on some tasks independently. For example, I practice forging and refining the core steel.

If there’s no core steel, I have to forge it myself. I’ve also had the opportunity to participate in the initial stages of blade tempering yakiire.

Instead of constantly asking my master for guidance, we discuss the work together, and I do more tasks on my own.

Working on tasks myself means I’m not always assisting my master.

(Instructor Mr.Kubo Zenbaku, from now on, it will be shown as “Master Kubo”) When I have things for him to do, I’ll assign them, but it’s not like there’s something to do all year round.

It’s not like a school with a curriculum where you learn everything step by step. Generally, a blacksmith is present, and the apprentice gradually assists with the work.

The apprentice needs to learn all the processes by themselves in the end. At the start, he couldn’t do much, so you began with cleaning and cutting charcoal.

But eventually, he progressed to making small knives and learning hammer techniques while forging. When he became proficient with the hammer, he started practicing forging.

He slowly increased his responsibilities and improved at each level. Now, he has been training for three years, and he’s quite skilled, but there’s still some time before he can handle the final stages like blade tempering.

(Q) So, in his spare time, Johan Leutwiler is doing a lot of trial and error on his own?

(Master Kubo) Giving instructions all the time can be challenging. I want to focus on my work. I do my work, and then, when necessary, I instruct the apprentice.

So, when Johann became capable of doing things himself, I only provide instructions when required.

(Q) In your fourth year now, Johann, what were your impressions when you first started your apprenticeship?

(Johann) Initially, what struck me the most was the artistic value of the swords.

In Europe, a sword is merely seen as a curved blade, but in Japan, there’s a clear distinction between the swords used in Iaido and those considered artistic pieces.

The price difference is significant, with Iaido swords costing around 300,000 to 400,000 yen and artistic swords reaching 2 to 3 million yen.

There’s very little information about these distinctions in Europe. So, I didn’t understand this difference when I first started, probably for the first two months.

I wasn’t aware of this distinction during my time in a Swiss dojo(hall), where I practiced Iaido.

I knew someone who had real swords, but now I realize that they were quite inexpensive. Perhaps people in Europe think that such affordable swords are “ordinary” swords.

I believe that the truly beautiful aspects of swords need to be more widely appreciated.

(Q) When you first saw artistic swords in person after arriving in Japan, did they differ significantly from the image you had in your mind up until then? Did you feel things like “Is metal really this beautiful?”

(Johann) Yes, I did. The most striking thing was not that the metal was beautiful but that I realized what human beings are capable of.

I was amazed by the craftsmanship of swordsmiths. Swords are something that even a novice can understand when they see and hold one.

Even without a professional’s perspective, you can quickly tell whether a sword is good. If it’s well-made, it’s good. If it’s rough, it has no value, and that’s immediately evident.

Before coming to Japan, I had read various books about swords, but this information wasn’t in them.

It wasn’t in books, so I had to do my own research in the beginning to understand why some swords couldn’t win awards and why they were so cheap, while swords made by my master and other bearers of intangible cultural heritage cost millions.

I didn’t grasp these distinctions during the first two months.

(Q) When you were practicing Iaido in Switzerland, were you not particularly conscious of these things?

(Johann) No, I wasn’t. I had read books in French, but they didn’t contain this kind of information, these distinctions.

I knew someone who owned real swords, but now I realize that they were quite cheap. Such inexpensive swords might be considered “ordinary” by people in Europe. I think we need to promote the real beauty of swords.

(Q) What was it like when you saw artistic swords for the first time in Japan, and did it significantly differ from the image of swords you had in your mind? Did you feel things like, “Can metal really be this beautiful?”

(Johann) Yes, exactly. The most significant impression was not that the iron was beautiful, but rather, I thought, “People can do this to this extent.”

I was just so impressed with swordsmiths. For instance, even someone who is not influenced by a professional perspective, when they see a sword, they can tell it’s good if it’s good.

Even if you’re a complete novice, if you see a sword and it’s a well-made sword, you know it’s good. You can tell right away. If it’s crude, you know it’s not valuable. I still think that’s amazing.

(Q) Kubo-sensei focuses on the Suguha style, but there are other styles, like Choji and other various types of Hamon (temper line) and Jihada (grain pattern). What aspects of swordsmithing do you find appealing?

(Johann) I think Choji is the coolest. My master also says, “If you can do both Choji and Suguha well, then you can probably achieve almost any Hamon you want.” So, that aspect is very interesting.

Both Suguha and Choji are impressive. I would like to try making both in the future.

(Q) What kind of swords would you like to create?

(Johann) I can’t provide a detailed answer because I haven’t created my own pieces yet, but what’s most important to me is to craft a sword that is cherished.

Swords are passed on to the next generation, so if they aren’t loved, their lifespan is limited, maybe around 30 years, even though originally they were designed to last for 1000 years.

So, it needs to be something people want to treasure.

No matter how good a sword is or how many awards it receives, if it doesn’t pass on to the next generation, it all ends there.

I hope to create a sword that anyone would appreciate.

Of course, the appearance and the quality of the steel are crucial, but more than that, it’s difficult to express in words, like I mentioned earlier, it’s about the feeling when you hold it.

About Foreigners Becoming Swordsmiths

(Q) Mr. Kubo, you’ve trained apprentices like Mr. Akechi Yosuke. What do you think about Mr. Johann Loitvillar from your perspective?

(Master Kubo) At first, I thought he would return to Switzerland soon, but he’s quite persistent. He would ask me every morning, “When are you leaving?”

(Johann) Every morning, yes. Every morning and every evening. There were times when he told me, “You don’t need to come tomorrow.” (laughs)

(Master Kubo) Well, if you’re going to quit, the sooner, the better.

(Johann)I didn’t plan to quit, so I got used to it.

(Master Kubo) No one has ever quit as my apprentice. There was one high school student who tried it for two weeks, but no one has ever quit as an apprentice.

In five years, they obtain their certification, and they get work, too. I believe I’ve taught them well enough to earn awards.

I was initially skeptical because he’s 28, and he had worked in a metal workshop. I thought that was quite late.

But he had physical strength, a sense of creating things, and he was ready. So, I decided to take him on as an apprentice.

(Q) At first, there might have been some surprises when a Swiss person arrived, right?

(Master Kubo) I organize a training program at the swordsmith association. There are many people who become apprentices but don’t improve, and there are many unfortunate people who work for ten years and still can’t support themselves even after getting certified.

So, I only recommend taking on apprentices who are genuinely motivated and talented. I even suggested it to Mr. Akechi and others.

They said, “No, it’s a waste,” so I decided to do it myself. Mr. Loitvillar seemed sincere, and he seemed to have a sense of craftsmanship.

So, I decided to take him on as an apprentice. When I did, I asked him when he would quit. (laughs)

In any case, you shouldn’t be overly kind to someone who wants to become a swordsmith. It’s a very challenging world once they become independent.

They have to sharpen swords, make scabbards, earn money, find customers, and at first, they might even get a few nicks in the blades.

They won’t have money to build a workshop, and it’s a tough situation. I know this because I’ve seen people who’ve quit.

So, as much as possible, I want to prepare them with some challenges before they start their journey alone.

(Johann) Every day, he asked me, “When will you quit?” And when I leave in the evening, he says, “But if you quit, I’ll hire a sniper to take care of you.”

(Master Kubo) I said when you go back to Switzerland, and then I said, “A sniper will take care of you.” (laughs)

(Johann) Well, I’d rather be killed with a sword than by a sniper. Snipers are sad.

(Master Kubo) Swords are an important part of Japanese culture, so we don’t need to teach all the essential techniques.

Once someone with those skills leaves, they don’t come back. He says he won’t return to Switzerland, so I plan to teach him enough to make a living as a swordsmith.

(Johann) I plan to naturalize after completing my apprenticeship. I’m currently training on a cultural activity visa.

I’m a bit worried about whether I can use the certification after training. If I naturalize, I’ll become a Japanese citizen and live like a regular person, so I need to be prepared for that level of commitment.

(Q) By the way, I don’t want to return to Switzerland, and my intention is to find a life here in Japan, but do you ever feel any discomfort about your Swiss identity?

(Johann) Well, I am technically Swiss, so there’s no problem with that. But when regular people see me write it that way, they might wonder when I’ll go back.

That was the only thing that bothered me a bit at first. Everyone would ask, “When are you going back?”

(Master Kubo) He used to get angry every time someone asked that. He got angry about it, even though it doesn’t have any deeper meaning.

(Johann) Yes, it’s just a cultural difference. In Switzerland, there are many foreigners, and if you ask a foreigner, “When are you going back?”

you’re picking a fight. It’s discrimination; it means, “We don’t want you here; when are you leaving?” It’s not a friendly question, so I used to get angry about it.

(Master Kubo) It’s just that people think that when a foreigner comes to Japan and learns a technique, they’ll return home. It’s not just my opinion; it’s a common pattern. It can’t be helped.

We hope that Johann Loitvillar continues to thrive in Japan.

(Master Kubo) He might end up returning in ten years, saying he’s going back to Switzerland. (laughs)

User

Oh Thank thank you very much for great job you’ve done. I thank you so much again. Have a nice day!

Although this video has not subscribed into English, would you please wait a little more? Thanks.